Naval Aviation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by

Early experiments on the use of kites for naval reconnaissance took place in 1903 at

Early experiments on the use of kites for naval reconnaissance took place in 1903 at  In January 1912, the British battleship took part in aircraft experiments at Sheerness. She was fitted for flying off aircraft with a downward-sloping runway which was installed on her foredeck, running over her forward

In January 1912, the British battleship took part in aircraft experiments at Sheerness. She was fitted for flying off aircraft with a downward-sloping runway which was installed on her foredeck, running over her forward

At the outbreak of war the Royal Naval Air Service had 93 aircraft, six

At the outbreak of war the Royal Naval Air Service had 93 aircraft, six

TB Torpedo Bomber. T Torpedo and bombing.

Retrieved on 29 September 2009. and in August 1915, a

The need for a more mobile strike capacity led to the development of the aircraft carrier - the backbone of modern naval aviation. was the first purpose-built seaplane carrier and was also arguably the first modern aircraft carrier. She was originally

The need for a more mobile strike capacity led to the development of the aircraft carrier - the backbone of modern naval aviation. was the first purpose-built seaplane carrier and was also arguably the first modern aircraft carrier. She was originally

Genuine aircraft carriers did not emerge beyond Britain until the early 1920s.

The Japanese (1921) was the world's first purpose-built aircraft carrier, although the initial plans and laying down for (1924) had begun earlier. Both ''Hōshō'' and ''Hermes'' initially boasted the two most distinctive features of a modern aircraft carrier: a full-length flight deck and a starboard-side control tower

Genuine aircraft carriers did not emerge beyond Britain until the early 1920s.

The Japanese (1921) was the world's first purpose-built aircraft carrier, although the initial plans and laying down for (1924) had begun earlier. Both ''Hōshō'' and ''Hermes'' initially boasted the two most distinctive features of a modern aircraft carrier: a full-length flight deck and a starboard-side control tower

During the Doolittle Raid of 1942, 16 Army Air Force, Army medium bombers were launched from the carrier ''Hornet'' on one-way missions to bomb Japan. All were lost to fuel exhaustion after bombing their targets and the experiment was not repeated. Smaller carriers were built in large numbers to escort slow cargo convoys or supplement fast carriers. Aircraft for observation or light raids were also carried by battleships and cruisers, while blimps were used to search for attack submarines.

Experience showed that there was a need for widespread use of aircraft which could not be met quickly enough by building new fleet aircraft carriers. This was particularly true in the North Atlantic, where convoys were highly vulnerable to U-boat attack. The British authorities used unorthodox, temporary, but effective means of giving air protection such as CAM ships and merchant aircraft carriers, merchant ships modified to carry a small number of aircraft. The solution to the problem were large numbers of mass-produced merchant hulls converted into escort aircraft carriers (also known as "jeep carriers"). These basic vessels, unsuited to fleet action by their capacity, speed and vulnerability, nevertheless provided air cover where it was needed.

The Royal Navy had observed the impact of naval aviation and, obliged to prioritise their use of resources, abandoned battleships as the mainstay of the fleet. was therefore the last British battleship and her sisters were cancelled. The United States had already instigated a large construction programme (which was also cut short) but these large ships were mainly used as anti-aircraft batteries or for Naval gunfire support, shore bombardment.

Other actions involving naval aviation included:

* Battle of the Atlantic, aircraft carried by low-cost escort carriers were used for antisubmarine patrol, defense, and attack.

* At the start of the Pacific War in 1941, Japanese carrier-based aircraft sank many US warships during the attack on Pearl Harbor and land-based aircraft Sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse, sank two large British warships. Engagements between Japanese and American naval fleets were then conducted largely or entirely by aircraft - examples include the battles of Battle of the Coral Sea, Coral Sea, Midway, Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Bismarck Sea and Battle of the Philippine Sea, Philippine Sea.Boyne (2003), pp.227–8

* Battle of Leyte Gulf, with the first appearance of kamikazes, perhaps the largest naval battle in history. Japan's last carriers and pilots are deliberately sacrificed, a Japanese battleship Musashi, battleship is sunk by aircraft.

* Operation Ten-Go demonstrated U.S. air supremacy in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater, Pacific theater by this stage in the war and the vulnerability of surface ships without air cover to aerial attack.

During the Doolittle Raid of 1942, 16 Army Air Force, Army medium bombers were launched from the carrier ''Hornet'' on one-way missions to bomb Japan. All were lost to fuel exhaustion after bombing their targets and the experiment was not repeated. Smaller carriers were built in large numbers to escort slow cargo convoys or supplement fast carriers. Aircraft for observation or light raids were also carried by battleships and cruisers, while blimps were used to search for attack submarines.

Experience showed that there was a need for widespread use of aircraft which could not be met quickly enough by building new fleet aircraft carriers. This was particularly true in the North Atlantic, where convoys were highly vulnerable to U-boat attack. The British authorities used unorthodox, temporary, but effective means of giving air protection such as CAM ships and merchant aircraft carriers, merchant ships modified to carry a small number of aircraft. The solution to the problem were large numbers of mass-produced merchant hulls converted into escort aircraft carriers (also known as "jeep carriers"). These basic vessels, unsuited to fleet action by their capacity, speed and vulnerability, nevertheless provided air cover where it was needed.

The Royal Navy had observed the impact of naval aviation and, obliged to prioritise their use of resources, abandoned battleships as the mainstay of the fleet. was therefore the last British battleship and her sisters were cancelled. The United States had already instigated a large construction programme (which was also cut short) but these large ships were mainly used as anti-aircraft batteries or for Naval gunfire support, shore bombardment.

Other actions involving naval aviation included:

* Battle of the Atlantic, aircraft carried by low-cost escort carriers were used for antisubmarine patrol, defense, and attack.

* At the start of the Pacific War in 1941, Japanese carrier-based aircraft sank many US warships during the attack on Pearl Harbor and land-based aircraft Sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse, sank two large British warships. Engagements between Japanese and American naval fleets were then conducted largely or entirely by aircraft - examples include the battles of Battle of the Coral Sea, Coral Sea, Midway, Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Bismarck Sea and Battle of the Philippine Sea, Philippine Sea.Boyne (2003), pp.227–8

* Battle of Leyte Gulf, with the first appearance of kamikazes, perhaps the largest naval battle in history. Japan's last carriers and pilots are deliberately sacrificed, a Japanese battleship Musashi, battleship is sunk by aircraft.

* Operation Ten-Go demonstrated U.S. air supremacy in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater, Pacific theater by this stage in the war and the vulnerability of surface ships without air cover to aerial attack.

Jet aircraft were used on aircraft carriers after the War. The first jet landing on a carrier was made by Eric "Winkle" Brown, Lt Cdr Eric "Winkle" Brown who landed on in the specially modified de Havilland Vampire United Kingdom military aircraft serials, LZ551/G on 3 December 1945. Following the introduction of Flight deck#Angled flight deck, angled flight decks, jets were regularly operating from carriers by the mid-1950s.

An important development of the early 1950s was the British invention of the angled flight deck by Capt D.R.F. Campbell RN in conjunction with Lewis Boddington of the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough. The runway was canted at an angle of a few degrees from the longitudinal axis of the ship. If an aircraft missed the arrestor cables (referred to as a "bolter (aviation), bolter"), the pilot only needed to increase engine power to maximum to get airborne again, and would not hit the parked aircraft because the angled deck pointed out over the sea. The angled flight deck was first tested on , by painting angled deck markings onto the centerline flight deck for touch and go landings. The modern Aircraft catapult, steam-powered catapult, powered by steam from a ship's boilers or reactors, was invented by Commander C.C. Mitchell of the Royal Naval Reserve. It was widely adopted following trials on between 1950 and 1952 which showed it to be more powerful and reliable than the hydraulic catapults which had been introduced in the 1940s. The first Optical Landing System, the Mirror landing aid, Mirror Landing Aid was invented by Lieutenant Commander H. C. N. Goodhart RN. The first trials of a mirror landing sight were conducted on HMS ''Illustrious'' in 1952.

The US Navy built the first aircraft carrier to be powered by nuclear reactors. was powered by eight nuclear reactors and was the second surface warship (after ) to be powered in this way. The post-war years also saw the development of the helicopter, with a variety of useful roles and mission capability aboard aircraft carriers and other naval ships. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the United Kingdom and the United States converted some older carriers into Commando Carriers or Landing Platform Helicopters (LPH); seagoing helicopter airfields like . To mitigate the expensive connotations of the term "aircraft carrier", the carriers were originally designated as "through deck cruisers" and were initially to operate as helicopter-only craft escort carriers.

The arrival of the Sea Harrier VTOL/STOVL fast jet meant that the Invincible-class could carry fixed-wing aircraft, despite their short flight decks. The British also introduced the ski-jump ramp as an alternative to contemporary catapult systems. As the Royal Navy retired or sold the last of its World War II-era carriers, they were replaced with smaller ships designed to operate helicopters and the V/STOVL Sea Harrier jet. The ski-jump gave the Harriers an enhanced STOVL capability, allowing them to take off with heavier payloads.

In 2013, the US Navy completed the first successful catapult launch and arrested landing of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) aboard an aircraft carrier. After a decade of research and planning, the US Navy has been testing the integration of UAVs with carrier-based forces since 2013, using the experimental Northrop Grumman X-47B, and is working to procure a fleet of carrier-based UAVs, referred to as the Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) system.

Jet aircraft were used on aircraft carriers after the War. The first jet landing on a carrier was made by Eric "Winkle" Brown, Lt Cdr Eric "Winkle" Brown who landed on in the specially modified de Havilland Vampire United Kingdom military aircraft serials, LZ551/G on 3 December 1945. Following the introduction of Flight deck#Angled flight deck, angled flight decks, jets were regularly operating from carriers by the mid-1950s.

An important development of the early 1950s was the British invention of the angled flight deck by Capt D.R.F. Campbell RN in conjunction with Lewis Boddington of the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough. The runway was canted at an angle of a few degrees from the longitudinal axis of the ship. If an aircraft missed the arrestor cables (referred to as a "bolter (aviation), bolter"), the pilot only needed to increase engine power to maximum to get airborne again, and would not hit the parked aircraft because the angled deck pointed out over the sea. The angled flight deck was first tested on , by painting angled deck markings onto the centerline flight deck for touch and go landings. The modern Aircraft catapult, steam-powered catapult, powered by steam from a ship's boilers or reactors, was invented by Commander C.C. Mitchell of the Royal Naval Reserve. It was widely adopted following trials on between 1950 and 1952 which showed it to be more powerful and reliable than the hydraulic catapults which had been introduced in the 1940s. The first Optical Landing System, the Mirror landing aid, Mirror Landing Aid was invented by Lieutenant Commander H. C. N. Goodhart RN. The first trials of a mirror landing sight were conducted on HMS ''Illustrious'' in 1952.

The US Navy built the first aircraft carrier to be powered by nuclear reactors. was powered by eight nuclear reactors and was the second surface warship (after ) to be powered in this way. The post-war years also saw the development of the helicopter, with a variety of useful roles and mission capability aboard aircraft carriers and other naval ships. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the United Kingdom and the United States converted some older carriers into Commando Carriers or Landing Platform Helicopters (LPH); seagoing helicopter airfields like . To mitigate the expensive connotations of the term "aircraft carrier", the carriers were originally designated as "through deck cruisers" and were initially to operate as helicopter-only craft escort carriers.

The arrival of the Sea Harrier VTOL/STOVL fast jet meant that the Invincible-class could carry fixed-wing aircraft, despite their short flight decks. The British also introduced the ski-jump ramp as an alternative to contemporary catapult systems. As the Royal Navy retired or sold the last of its World War II-era carriers, they were replaced with smaller ships designed to operate helicopters and the V/STOVL Sea Harrier jet. The ski-jump gave the Harriers an enhanced STOVL capability, allowing them to take off with heavier payloads.

In 2013, the US Navy completed the first successful catapult launch and arrested landing of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) aboard an aircraft carrier. After a decade of research and planning, the US Navy has been testing the integration of UAVs with carrier-based forces since 2013, using the experimental Northrop Grumman X-47B, and is working to procure a fleet of carrier-based UAVs, referred to as the Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) system.

* Brazilian Naval Aviation (Brazilian Navy)

* People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force (People's Liberation Army Navy, Chinese People's Liberation Army Navy)

* Republic of China Naval Aviation Command (Republic of China Navy)

* Chilean Navy#Aircraft inventory, Chilean Naval Aviation (Chilean Navy)

* Colombian Navy#Aircraft, Colombian Naval Aviation (Colombian Navy)

* Flotilla de Aeronaves (FLOAN) (Spanish Navy)

* French Naval Aviation (French Navy)

* Marineflieger (German Navy)

* Navy Aviation Command (Hellenic Navy)

* Indian Naval Air Arm (Indian Navy)

* Indonesian Navy Aviation Center (Indonesian Navy)

* Islamic Republic of Iran Navy Aviation (Islamic Republic of Iran Navy)

* Italian Naval Aviation (Italian Navy)

* Fleet Air Force (JMSDF), Fleet Air Force (Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force)

* Republic of Korea Navy#Republic of Korea Fleet, Air Wing Six (Republic of Korea Navy)

* Mexican Naval Aviation (Mexican Navy)

* Pakistan Naval Air Arm (Pakistan Navy)

* Peruvian Naval Aviation (Peruvian Navy)

* Polish Navy#Ships and naval aircraft, Polish Naval Aviation (Polish Navy)

* Brazilian Naval Aviation (Brazilian Navy)

* People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force (People's Liberation Army Navy, Chinese People's Liberation Army Navy)

* Republic of China Naval Aviation Command (Republic of China Navy)

* Chilean Navy#Aircraft inventory, Chilean Naval Aviation (Chilean Navy)

* Colombian Navy#Aircraft, Colombian Naval Aviation (Colombian Navy)

* Flotilla de Aeronaves (FLOAN) (Spanish Navy)

* French Naval Aviation (French Navy)

* Marineflieger (German Navy)

* Navy Aviation Command (Hellenic Navy)

* Indian Naval Air Arm (Indian Navy)

* Indonesian Navy Aviation Center (Indonesian Navy)

* Islamic Republic of Iran Navy Aviation (Islamic Republic of Iran Navy)

* Italian Naval Aviation (Italian Navy)

* Fleet Air Force (JMSDF), Fleet Air Force (Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force)

* Republic of Korea Navy#Republic of Korea Fleet, Air Wing Six (Republic of Korea Navy)

* Mexican Naval Aviation (Mexican Navy)

* Pakistan Naval Air Arm (Pakistan Navy)

* Peruvian Naval Aviation (Peruvian Navy)

* Polish Navy#Ships and naval aircraft, Polish Naval Aviation (Polish Navy)  * Portuguese Naval Aviation (Portuguese Navy)

* Russian Naval Aviation (Russian Navy)

* Royal Thai Naval Air Division (Royal Thai Navy)

* Turkish Naval Aviation (Turkish Navy)

* Ukrainian Naval Aviation (Ukrainian Navy)

* Fleet Air Arm (United Kingdom

* Portuguese Naval Aviation (Portuguese Navy)

* Russian Naval Aviation (Russian Navy)

* Royal Thai Naval Air Division (Royal Thai Navy)

* Turkish Naval Aviation (Turkish Navy)

* Ukrainian Naval Aviation (Ukrainian Navy)

* Fleet Air Arm (United Kingdom

partly online

Full text (775 pages) public domain edition is also availabl

. * Ireland, Bernard. '' The History of Aircraft Carriers: An authoritative guide to 100 years of aircraft carrier development'' (2008) * Polmar, Norman. ''Aircraft carriers;: A graphic history of carrier aviation and its influence on world events'' (1969) * Polmar, Norman. ''Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events'' (2nd ed. 2 vol 2006) * Polmar, Norman, ed. ''Historic Naval Aircraft: The Best of "Naval History" Magazine'' (2004) * Smith, Douglas, V. ''One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Air Power'' (2010) * Trimble, William F. ''Hero of the Air: Glenn Curtiss and the Birth of Naval Aviation'' (2010)

excerpt and text search

* Lundstrom, John B. ''The First Team: Pacific Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway'' (2005

excerpt and text search

* Clark G. Reynolds, Reynolds, Clark G., ''The fast carriers: the forging of an air navy'' (3rd ed. 1992) * Reynolds, Clark G. '' On the Warpath in the Pacific: Admiral Jocko Clark and the Fast Carriers'' (2005

excerpt and text search

* Symonds, Craig L. ''The Battle of Midway'' (2011

excerpt and text search

* Tillman, Barrett. ''Enterprise: America's Fightingest Ship and the Men Who Helped Win World War II'' (2012

excerpt and text search

- A comprehensive history from the U.S. Naval Historical Center {{DEFAULTSORT:Naval Aviation Naval aviation,

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by navies

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

, whether from warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster a ...

s that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

. Carrier-based aircraft

Carrier-based aircraft, sometimes known as carrier-capable aircraft or carrier-borne aircraft, are naval aircraft designed for operations from aircraft carriers. They must be able to launch in a short distance and be sturdy enough to withstand ...

must be sturdy enough to withstand demanding carrier operations. They must be able to launch in a short distance and be sturdy and flexible enough to come to a sudden stop on a pitching flight deck; they typically have robust folding mechanisms that allow higher numbers of them to be stored in below-decks hangars and small spaces on flight decks. These aircraft are designed for many purposes, including air-to-air combat

Air combat manoeuvring (also known as ACM or dogfighting) is the tactical art of moving, turning and/or situating one's fighter aircraft in order to attain a position from which an attack can be made on another aircraft. Air combat manoeuvres ...

, surface attack, submarine attack, search and rescue

Search and rescue (SAR) is the search for and provision of aid to people who are in distress or imminent danger. The general field of search and rescue includes many specialty sub-fields, typically determined by the type of terrain the search ...

, matériel transport, weather observation

Weather reconnaissance is the acquisition of weather data used for research and planning. Typically the term reconnaissance refers to observing weather from the air, as opposed to the ground.

Methods

Aircraft

Helicopters are not built to w ...

, reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

and wide area command and control

Command and control (abbr. C2) is a "set of organizational and technical attributes and processes ... hatemploys human, physical, and information resources to solve problems and accomplish missions" to achieve the goals of an organization or en ...

duties.

Naval helicopters can be used for many of the same missions as fixed-wing aircraft

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air flying machine, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using wings that generate lift caused by the aircraft's forward airspeed and the shape of the wings. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinc ...

while operating from aircraft carriers, helicopter carrier

A helicopter carrier is a type of aircraft carrier whose primary purpose is to operate helicopters, and has a large flight deck that occupies a substantial part of the deck, which can extend the full length of the ship like of the Royal Navy ...

s, destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s.

History

Establishment

Early experiments on the use of kites for naval reconnaissance took place in 1903 at

Early experiments on the use of kites for naval reconnaissance took place in 1903 at Woolwich Common

Woolwich Common is a common in Woolwich in southeast London, England. It is partly used as military land (less than 40%) and partly as an urban park. Woolwich Common is a conservation area. It is part of the South East London Green Chain. It is al ...

for the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

. Samuel Franklin Cody

Samuel Franklin Cowdery (later known as Samuel Franklin Cody; 6 March 1867 – 7 August 1913, born Davenport, Iowa, USA)) was a Wild West showman and early pioneer of manned flight. He is most famous for his work on the large kites known a ...

demonstrated the capabilities of his 8-foot-long black kite and it was proposed for use as either a mechanism to hold up wires for wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

communications or as a manned reconnaissance device that would give the viewer the advantage of considerable height.

In 1908 Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

approved the formation of an "Aerial Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence" to investigate the potential for naval aviation. In 1909 this body accepted the proposal of Captain Reginald Bacon

Admiral Sir Reginald Hugh Spencer Bacon, (6 September 1863 – 9 June 1947) was an officer in the Royal Navy noted for his technical abilities. He was described by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Jacky Fisher, as the man "acknowledged to be the ...

made to the First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed Fo ...

Sir John Fisher

John Arbuthnot Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher, (25 January 1841 – 10 July 1920), commonly known as Jacky or Jackie Fisher, was a British Admiral of the Fleet. With more than sixty years in the Royal Navy, his efforts to reform the service helped t ...

that rigid airships should be constructed for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

to be used for reconnaissance. This resulted in the construction of ''Mayfly

Mayflies (also known as shadflies or fishflies in Canada and the upper Midwestern United States, as Canadian soldiers in the American Great Lakes region, and as up-winged flies in the United Kingdom) are aquatic insects belonging to the ord ...

'' in 1909, the first air component of the navy to become operational, and the genesis of modern naval aviation.

The first pilots for the Royal Navy were transferred from the Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

in June 1910 along with two aircraft with which to train new pilots, and an airfield at Eastchurch

Eastchurch is a village and civil parish on the Isle of Sheppey, in the English county of Kent, two miles east of Minster. The village website claims the area has "a history steeped in stories of piracy and smugglers".

Aviation history

Eastch ...

became the Naval Flying School, the first such facility in the world. Two hundred applications were received, and four were accepted: Lieutenant C R Samson, Lieutenant A M Longmore, Lieutenant A Gregory and Captain E L Gerrard, RMLI.

The French also established a naval aviation capability in 1910 with the establishment of the Service Aeronautique and the first flight training schools.

U.S. naval aviation began with pioneer aviator Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early a ...

who contracted with the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

to demonstrate that airplanes could take off from and land aboard ships at sea. One of his pilots, Eugene Ely

Eugene Burton Ely (October 21, 1886 – October 19, 1911) was an American aviation pioneer, credited with the first shipboard aircraft take off and landing.

Background

Ely was born in Williamsburg, Iowa, and raised in Davenport, Iowa. Having c ...

, took off from the cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

anchored off the Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

coast in November 1910. Two months later Ely landed aboard another cruiser, , in San Francisco Bay, proving the concept of shipboard operations. However, the platforms erected on those vessels were temporary measures. The U.S. Navy and Glenn Curtiss experienced two firsts during January 1911. On 27 January, Curtiss flew the first seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

from the water at San Diego Bay and the next day U.S. Navy Lt. Theodore G. Ellyson, a student at the nearby Curtiss School, took off in a Curtiss "grass cutter" plane to become the first naval aviator.

$25,000 was appropriated for the Bureau of Navigation (United States Navy) to purchase three airplanes and in the spring of 1911 four additional officers were trained as pilots by the Wright brothers and Curtiss. A camp with a primitive landing field was established on the Severn River at Greenbury Point, near Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

. The vision of the aerial fleet was for scouting. Each aircraft would have a pilot and observer. The observer would use the wireless radio technology to report on enemy ships. Some thoughts were given to deliver counterattacks on hostile aircraft using “explosives or other means”. Using airplanes to bomb ships was seen as largely impractical at the time. CAPT Washington Irving Chambers

Captain Washington Irving Chambers, USN (April 4, 1856 – September 23, 1934) was a 43-year, career United States Navy officer, who near the end of his service played a major role in the early development of U.S.Naval aviation, serving as the fir ...

felt it was much easier to defend against airplanes than mines or torpedoes. The wireless radio was cumbersome (greater than 50 pounds), but the technology was improving. Experiments were underway for the first ICS (pilot to observer comms) using headsets, as well as connecting the observer to the radio. The navy tested both telephones and voice tubes for ICS. As of August 1911, Italy was the only other navy known to be adapting hydroplanes for naval use.

The group expanded with the addition of six aviators in 1912 and five in 1913, from both the Navy and Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

, and conducted maneuvers with the Fleet from the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

, designated as the Navy's aviation ship. Meanwhile, Captain Henry C. Mustin successfully tested the concept of the catapult launch in August 1912, and in 1915 made the first catapult launching from a ship underway. The first permanent naval air station was established at Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ...

, in January 1914 with Mustin as its commanding officer. On April 24 of that year, and for a period of approximately 45 days afterward, five floatplanes and flying boats

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

flown by ten aviators operated from ''Mississippi'' and the cruiser ''Birmingham'' off Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

and Tampico

Tampico is a city and port in the southeastern part of the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico. It is located on the north bank of the Pánuco River, about inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and directly north of the state of Veracruz. Tampico is the fifth ...

, Mexico, respectively, conducting reconnaissance for troops ashore in the wake of the Tampico Affair

The Tampico Affair began as a minor incident involving U.S. Navy sailors and the Mexican Federal Army loyal to Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta. On April 9, 1914, nine sailors had come ashore to secure supplies and were detained by M ...

.

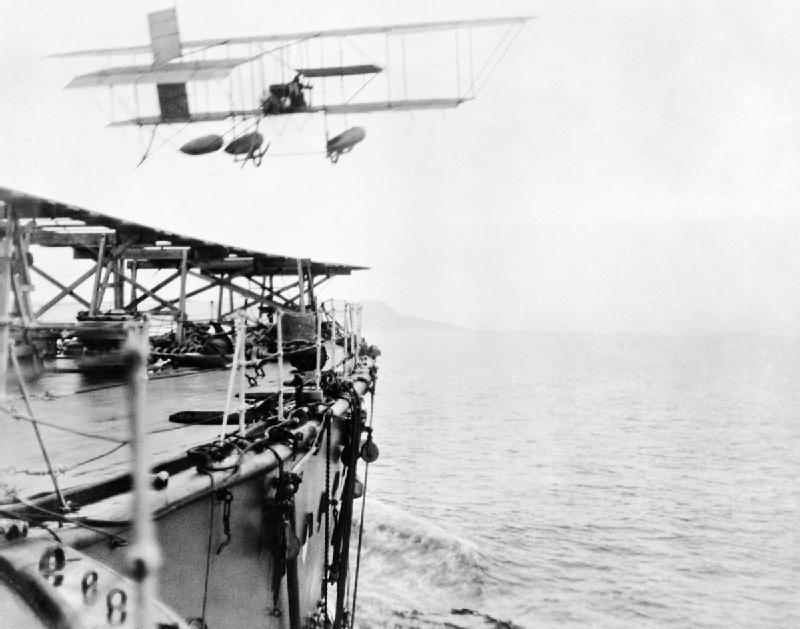

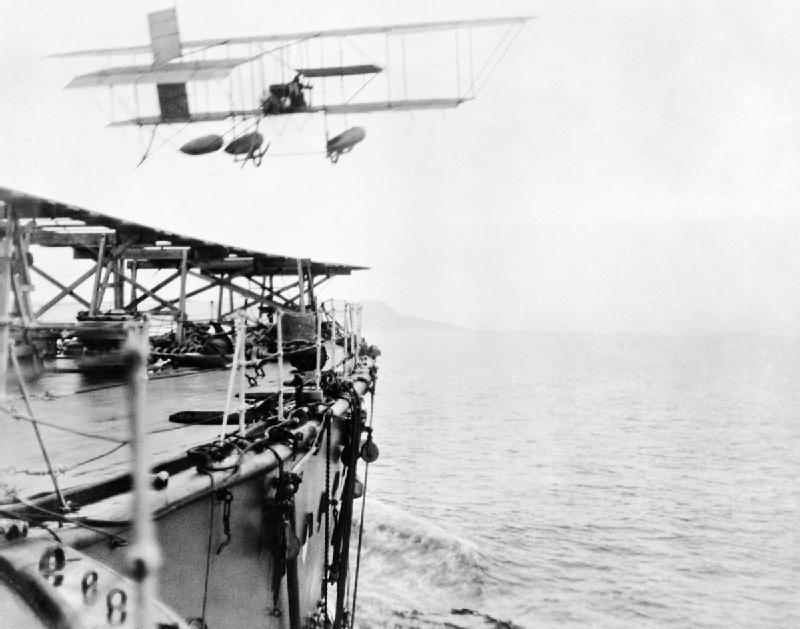

In January 1912, the British battleship took part in aircraft experiments at Sheerness. She was fitted for flying off aircraft with a downward-sloping runway which was installed on her foredeck, running over her forward

In January 1912, the British battleship took part in aircraft experiments at Sheerness. She was fitted for flying off aircraft with a downward-sloping runway which was installed on her foredeck, running over her forward gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

from her forebridge to her bow and equipped with rails to guide the aircraft. The Gnome-engined Short Improved S.27

The Short S.27 and its derivative, the Short Improved S.27 (sometimes called the Short-Sommer biplane), were a series of early British aircraft built by Short Brothers. They were used by the Admiralty and Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps fo ...

"S.38", pusher seaplane piloted by Lieutenant Charles Samson

Air Commodore Charles Rumney Samson, (8 July 1883 – 5 February 1931) was a British naval aviation pioneer. He was one of the first four officers selected for pilot training by the Royal Navy and was the first person to fly an aircraft fr ...

become the first British aircraft to take-off from a ship while at anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek ἄγ ...

in the River Medway

The River Medway is a river in South East England. It rises in the High Weald AONB, High Weald, East Sussex and flows through Tonbridge, Maidstone and the Medway conurbation in Kent, before emptying into the Thames Estuary near Sheerness, a to ...

, on 10 January 1912. ''Africa'' then transferred her flight equipment to her sister ship .

In May 1912, with Commander Samson again flying the "S.38", the first ever instance of an aircraft to take off from a ship which was under way occurred. ''Hibernia'' steamed at at the Royal Fleet Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

in Weymouth Bay

Weymouth Bay is a sheltered bay on the south coast of England, in Dorset. It is protected from erosion by Chesil Beach and the Isle of Portland, and includes several beaches, notably Weymouth Beach, a gently curving arc of golden sand which st ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. ''Hibernia'' then transferred her aviation equipment to battleship . Based on these experiments, the Royal Navy concluded that aircraft were useful aboard ship for spotting and other purposes, but that interference with the firing of guns caused by the runway built over the foredeck and the danger and impracticality of recovering seaplanes that alighted in the water in anything but calm weather more than offset the desirability of having airplanes aboard. In 1912, the nascent naval air detachment in the United Kingdom was amalgamated to form the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

and in 1913 a seaplane base on the Isle of Grain

Isle of Grain (Old English ''Greon'', meaning gravel) is a village and the easternmost point of the Hoo Peninsula within the district of Medway in Kent, south-east England. No longer an island and now forming part of the peninsula, the area i ...

, an airship base at Kingsnorth

Kingsnorth is a mixed rural and urban village and relatively large civil parish adjoining Ashford in Kent, England. The civil parish includes the district of Park Farm.

Features

The Greensand Way, a long distance footpath stretching from Hasl ...

and eight new airfields were approved for construction. The first aircraft participation in naval manoeuvres took place in 1913 with the cruiser converted into a seaplane carrier

A seaplane tender is a boat or ship that supports the operation of seaplanes. Some of these vessels, known as seaplane carriers, could not only carry seaplanes but also provided all the facilities needed for their operation; these ships are rega ...

. In 1914, naval aviation was split again, and became the Royal Naval Air Service. However, shipboard naval aviation had begun in the Royal Navy, and would become a major part of fleet operations by 1917.

Other early operators of seaplanes were Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, within its ''Marine-Fliegerabteilung'' naval aviation units within the ''Kaiserliche Marine'', and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. In May 1913 Germany established a naval zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

detachment in Berlin-Johannisthal

Johannisthal () is a German locality (''Ortsteil'') within the Berlin borough (''Bezirk'') of Treptow-Köpenick. Until 2001 it was part of the former borough of Treptow.

History

The first mention of the locality dates from November 16, 1753. In 1 ...

and an airplane squadron in Putzig (Puck, Poland)."Marineflieger: Als Wilhelm II. seiner Flotte das Fliegen befahl"Die Welt

''Die Welt'' ("The World") is a German national daily newspaper, published as a broadsheet by Axel Springer SE.

''Die Welt'' is the flagship newspaper of the Axel Springer publishing group. Its leading competitors are the ''Frankfurter Allg ...

, 6 May 2013, The Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

established the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service, modelled on the RNAS

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

, in 1913. On 24 January 1913 came the first wartime naval aviation interservice cooperation mission. Greek pilots on a seaplane observed and drew a diagram of the positions of the Turkish fleet against which they dropped four bombs. This event was widely commented upon in the press, both Greek and international.

World War I

At the outbreak of war the Royal Naval Air Service had 93 aircraft, six

At the outbreak of war the Royal Naval Air Service had 93 aircraft, six airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

s, two balloons and 727 personnel, making it larger than the Royal Flying Corps. The main roles of the RNAS were fleet reconnaissance, patrolling coasts for enemy ships and submarines, attacking enemy coastal territory and defending Britain from enemy air-raids, along with deployment along the Western Front. In 1914 the first aerial torpedo was dropped in trials performed in a Short "Folder" by Lieutenant (later Air Chief Marshal Sir) Arthur Longmore

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Murray Longmore, (8 October 1885 – 10 December 1970) was an early naval aviator, before reaching high rank in the Royal Air Force. He was Commander-in-Chief of the RAF's Middle East Command from 1940 to 1941.

E ...

,GlobalSecurity.org. MilitaryTB Torpedo Bomber. T Torpedo and bombing.

Retrieved on 29 September 2009. and in August 1915, a

Short Type 184

The Short Admiralty Type 184, often called the Short 225 after the power rating of the engine first fitted, was a British two-seat reconnaissance, bombing and torpedo carrying folding-wing seaplane designed by Horace Short of Short Brothers. It ...

piloted by Flight Commander Charles Edmonds

Air Vice Marshal Charles Humphrey Kingsman Edmonds, (20 April 1891 – 26 September 1954) was an air officer of the Royal Air Force (RAF).

He first served in the Royal Navy and was a naval aviator during the First World War, taking part in the ...

from sank a Turkish supply ship in the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

with a , torpedo.

The first strike from a seaplane carrier against a land target as well as a sea target took place in September 1914 when the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrend ...

carrier conducted ship-launched air raids from Kiaochow Bay

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and Kiautschou in German.

Geogra ...

during the Battle of Tsingtao

The siege of Tsingtao (or Tsingtau) was the attack on the German port of Tsingtao (now Qingdao) in China during World War I by Japan and the United Kingdom. The siege was waged against Imperial Germany between 27 August and 7 November 191 ...

in China. The four Maurice Farman

Maurice Alain Farman (21 March 1877 – 25 February 1964) was a British-French Grand Prix motor racing champion, an aviator, and an aircraft manufacturer and designer.

Biography

Born in Paris to English parents, he and his brothers Richard and ...

seaplanes bombarded German-held land targets (communication centers and command centers) and damaged a German minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing controll ...

in the Tsingtao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

peninsula from September until 6 November 1914, when the Germans surrendered. One Japanese plane was credited being shot down by the German aviator Gunther Plüschow

Gunther Plüschow (February 8, 1886 – January 28, 1931) was a German aviator, aerial explorer and author from Munich, Bavaria. His feats include the only escape by a German prisoner of war in World War I from Britain back to Germany; he was ...

in an Etrich Taube

The Etrich ''Taube'', also known by the names of the various later manufacturers who built versions of the type, such as the Rumpler ''Taube'', was a pre-World War I monoplane aircraft. It was the first military aeroplane to be mass-produced in ...

, using his pistol.

On the Western front the first naval air raid occurred on 25 December 1914 when twelve seaplanes from , and ( cross-channel steamers converted into seaplane carriers) attacked the Zeppelin base at Cuxhaven. The raid was not a complete success, owing to sub-optimal weather conditions, including fog and low cloud, but the raid was able to conclusively demonstrate the feasibility of air-to-land strikes from a naval platform. Two German airships were destroyed at the Tøndern base on July 19, 1918, by seven Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel is a British First World War single-seat biplane fighter aircraft that was introduced on the Western Front in 1917. It was developed by the Sopwith Aviation Company as a successor to the Sopwith Pup and became one of the b ...

s launched from the carrier .

In August 1914 Germany operated 20 planes and one Zeppelin, another 15 planes were confiscated. They operated from bases in Germany and Flanders (Belgium). On 19 August 1918 several British torpedo boats were sunk by 10 German planes near Heligoland. These are considered as the first naval units solely destroyed by airplanes. During the war the German "Marineflieger" claimed the destruction of 270 enemy planes, 6 balloons, 2 airships, 1 Russian destroyer, 4 merchant ships, 3 submarines, 4 torpedo boats and 12 vehicles, for the loss of 170 German sea and land planes as well as 9 vehicles. Notable Marineflieger aces were Gotthard Sachsenberg

Gotthard Sachsenberg (6 December 1891 – 23 August 1961) was a German World War I fighter ace with 31 victories who went on to command the world's first naval air wing. In later life, he founded the airline ''Deutscher Aero Lloyd'', became an an ...

(31 victories), Alexander Zenzes

''Vizeflugmeister'' Alexander Zenzes (10 July 1898–September 1980) IC was a German World War I flying ace. He was a German naval pilot credited with 19 confirmed aerial victories.

After World War I, he gained a Doctorate in Engineering. In ...

(18 victories), Friedrich Christiansen

Friedrich Christiansen (12 December 1879 – 3 December 1972) was a German general who served as commander of the German ''Wehrmacht'' in the occupied Netherlands during World War II.

Christiansen was a World War I flying ace and the only seap ...

(13 victories, 1 airship and 1 submarine), Karl Meyer (8 victories), Karl Scharon (8 victories), and Hans Goerth

Vizeflugmeister Hans Goerth was a World War I German flying ace credited with seven confirmed aerial victories. He was the top ace of Marine Feld Jasta III (MFJ III) of the German Naval Air Service, and was one of the few aces allowed to fly the F ...

(7 victories).

Development of the aircraft carrier

The need for a more mobile strike capacity led to the development of the aircraft carrier - the backbone of modern naval aviation. was the first purpose-built seaplane carrier and was also arguably the first modern aircraft carrier. She was originally

The need for a more mobile strike capacity led to the development of the aircraft carrier - the backbone of modern naval aviation. was the first purpose-built seaplane carrier and was also arguably the first modern aircraft carrier. She was originally laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

as a merchant ship, but was converted on the building stocks to be a hybrid airplane/seaplane carrier with a launch platform and the capacity to hold up to four wheeled aircraft. Launched on 5 September 1914, she served in the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

campaign and throughout World War I.

During World War I the Royal Navy also used HMS ''Furious'' to experiment with the use of wheeled aircraft on ships. This ship was reconstructed three times between 1915 and 1925: first, while still under construction, it was modified to receive a flight deck

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the landing area for helicopte ...

on the fore-deck; in 1917 it was reconstructed with separate flight decks fore and aft of the superstructure; then finally, after the war, it was heavily reconstructed with a three-quarter length main flight deck, and a lower-level take-off only flight deck on the fore-deck.

On 2 August 1917, Squadron Commander E.H. Dunning, Royal Navy, landed his Sopwith Pup

The Sopwith Pup is a British single-seater biplane fighter aircraft built by the Sopwith Aviation Company. It entered service with the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps in the autumn of 1916. With pleasant flying character ...

aircraft on ''Furious'' in Scapa Flow, Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

, becoming the first person ''to land'' a plane on a moving ship. He was killed five days later during another landing on ''Furious''.

was converted from an ocean liner and became the first example of what is now the standard pattern of aircraft carrier, with a full-length flight deck that allowed wheeled aircraft to take off and land. After commissioning, the ship was heavily involved for several years in the development of the optimum design for other aircraft carriers. ''Argus'' also evaluated various types of arresting gear

An arresting gear, or arrestor gear, is a mechanical system used to rapidly decelerate an aircraft as it lands. Arresting gear on aircraft carriers is an essential component of naval aviation, and it is most commonly used on CATOBAR and STOB ...

, general procedures needed to operate a number of aircraft in concert, and fleet tactics.

The Tondern raid

The Tondern raid or Operation F.7, was a British bombing raid mounted by the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force against the Imperial German Navy airship base at Tønder, Denmark, then a part of Germany. The airships were used for the strategic bombin ...

, a British bombing raid against the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

's airship base at Tønder

Tønder (; german: Tondern ) is a town in the Region of Southern Denmark. With a population of 7,505 (as of 1 January 2022), it is the main town and the administrative seat of the Tønder Municipality.

History

The first mention of Tønder might ...

, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

was the first attack in history made by aircraft flying from a carrier flight deck, with seven Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel is a British First World War single-seat biplane fighter aircraft that was introduced on the Western Front in 1917. It was developed by the Sopwith Aviation Company as a successor to the Sopwith Pup and became one of the b ...

s launched from HMS ''Furious''. For the loss of one man, the British destroyed two German zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

s, L.54 and L.60 and a captive balloon.

Interwar period

Genuine aircraft carriers did not emerge beyond Britain until the early 1920s.

The Japanese (1921) was the world's first purpose-built aircraft carrier, although the initial plans and laying down for (1924) had begun earlier. Both ''Hōshō'' and ''Hermes'' initially boasted the two most distinctive features of a modern aircraft carrier: a full-length flight deck and a starboard-side control tower

Genuine aircraft carriers did not emerge beyond Britain until the early 1920s.

The Japanese (1921) was the world's first purpose-built aircraft carrier, although the initial plans and laying down for (1924) had begun earlier. Both ''Hōshō'' and ''Hermes'' initially boasted the two most distinctive features of a modern aircraft carrier: a full-length flight deck and a starboard-side control tower island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

. Both continued to be adjusted in the light of further experimentation and experience, however: ''Hōshō'' even opted to remove its island entirely in favor of a less obstructed flight deck and improved pilot visibility. Instead, Japanese carriers opted to control their flight operations from a platform extending from the side of the flight deck.

In the United States, Admiral William Benson attempted to entirely dissolve the USN's Naval Aeronautics program in 1919. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and others succeeded in maintaining it, but the service continued to support battleship-based doctrines. To counter Billy Mitchell

William Lendrum Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army officer who is regarded as the father of the United States Air Force.

Mitchell served in France during World War I and, by the conflict's end, command ...

's campaign to establish a separate Department of Aeronautics, Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Josephus Daniels ordered a rigged test against in 1920 which reached the conclusion that "the entire experiment pointed to the improbability of a modern battleship being either destroyed or completely put out of action by aerial bombs." Investigation by the ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' that discovered the rigging led to Congressional resolutions compelling more honest studies. The sinking of involved violating the Navy's rules of engagement

Rules of engagement (ROE) are the internal rules or directives afforded military forces (including individuals) that define the circumstances, conditions, degree, and manner in which the use of force, or actions which might be construed as pro ...

but completely vindicated Mitchell to the public. Some men, such as Captain (soon Rear Admiral) William A. Moffett

William Adger Moffett (October 31, 1869 – April 4, 1933) was an American admiral and Medal of Honor recipient known as the architect of naval aviation in the United States Navy.

Biography

Born October 31, 1869 in Charleston, South Carolina, ...

, saw the publicity stunt as a means to increase funding and support for the Navy's aircraft carrier projects. Moffett was sure that he had to move decisively in order to avoid having his fleet air arm fall into the hands of a proposed combined Land/Sea Air Force which took care of ''all'' the United States's airpower needs. (That very fate had befallen the two air services of the United Kingdom in 1918: the Royal Flying Corps had been combined with the Royal Naval Air Service to become the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, a condition which would remain until 1937.) Moffett supervised the development of naval air tactics throughout the '20s. The first aircraft carrier entered the U.S. fleet with the conversion of the collier USS ''Jupiter'' and its recommissioning as in 1922.

Many British naval vessels carried float planes, seaplanes or amphibians for reconnaissance and spotting: two to four on battleships or battlecruisers and one on cruisers. The aircraft, a Fairey Seafox

The Fairey Seafox was a 1930s British reconnaissance floatplane designed and built by Fairey for the Fleet Air Arm. It was designed to be catapulted from the deck of a light cruiser and served in the Second World War. Sixty-six were built, w ...

or later a Supermarine Walrus, were catapult-launched, and landed on the sea alongside for recovery by crane. Several submarine aircraft carriers

A submarine aircraft carrier is a submarine equipped with aircraft for observation or attack missions. These submarines saw their most extensive use during World War II, although their operational significance remained rather small. The most fa ...

were built by Japan, each carrying one floatplane, which did not prove effective in war. The French Navy built one large submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

, , which also carried one floatplane, and was also not effective in war.

World War II

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

saw the emergence of naval aviation as the decisive element in the war at sea. The principal users were Japan, United States (both with Pacific interests to protect) and Britain. Germany, the Soviet Union, France and Italy had a lesser involvement. Soviet Naval Aviation was mostly organised as land-based coastal defense force (apart from some scout floatplanes it consisted almost exclusively of land-based types also used by its air arms).

During the course of the war, seaborne aircraft were used in fleet actions at sea (Battle of Midway, Midway, ), strikes against naval units in port (Battle of Taranto, Taranto, Attack on Pearl Harbor, Pearl Harbor), support of ground forces (Battle of Okinawa, Okinawa, Allied invasion of Italy) and anti-submarine warfare (the Battle of the Atlantic). Carrier-based aircraft

Carrier-based aircraft, sometimes known as carrier-capable aircraft or carrier-borne aircraft, are naval aircraft designed for operations from aircraft carriers. They must be able to launch in a short distance and be sturdy enough to withstand ...

were specialised as dive bombers, torpedo bombers, and Fighter aircraft, fighters. Surface-based aircraft such as the PBY Catalina helped finding submarines and surface fleets.

In World War II the aircraft carrier replaced the battleship as the most powerful naval offensive weapons system as battles between fleets were increasingly fought out of gun range by aircraft. The Japanese , the most powerful battleship ever built, was first turned back by light escort carrier aircraft and later sunk lacking its own air cover.

During the Doolittle Raid of 1942, 16 Army Air Force, Army medium bombers were launched from the carrier ''Hornet'' on one-way missions to bomb Japan. All were lost to fuel exhaustion after bombing their targets and the experiment was not repeated. Smaller carriers were built in large numbers to escort slow cargo convoys or supplement fast carriers. Aircraft for observation or light raids were also carried by battleships and cruisers, while blimps were used to search for attack submarines.

Experience showed that there was a need for widespread use of aircraft which could not be met quickly enough by building new fleet aircraft carriers. This was particularly true in the North Atlantic, where convoys were highly vulnerable to U-boat attack. The British authorities used unorthodox, temporary, but effective means of giving air protection such as CAM ships and merchant aircraft carriers, merchant ships modified to carry a small number of aircraft. The solution to the problem were large numbers of mass-produced merchant hulls converted into escort aircraft carriers (also known as "jeep carriers"). These basic vessels, unsuited to fleet action by their capacity, speed and vulnerability, nevertheless provided air cover where it was needed.

The Royal Navy had observed the impact of naval aviation and, obliged to prioritise their use of resources, abandoned battleships as the mainstay of the fleet. was therefore the last British battleship and her sisters were cancelled. The United States had already instigated a large construction programme (which was also cut short) but these large ships were mainly used as anti-aircraft batteries or for Naval gunfire support, shore bombardment.

Other actions involving naval aviation included:

* Battle of the Atlantic, aircraft carried by low-cost escort carriers were used for antisubmarine patrol, defense, and attack.

* At the start of the Pacific War in 1941, Japanese carrier-based aircraft sank many US warships during the attack on Pearl Harbor and land-based aircraft Sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse, sank two large British warships. Engagements between Japanese and American naval fleets were then conducted largely or entirely by aircraft - examples include the battles of Battle of the Coral Sea, Coral Sea, Midway, Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Bismarck Sea and Battle of the Philippine Sea, Philippine Sea.Boyne (2003), pp.227–8

* Battle of Leyte Gulf, with the first appearance of kamikazes, perhaps the largest naval battle in history. Japan's last carriers and pilots are deliberately sacrificed, a Japanese battleship Musashi, battleship is sunk by aircraft.

* Operation Ten-Go demonstrated U.S. air supremacy in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater, Pacific theater by this stage in the war and the vulnerability of surface ships without air cover to aerial attack.

During the Doolittle Raid of 1942, 16 Army Air Force, Army medium bombers were launched from the carrier ''Hornet'' on one-way missions to bomb Japan. All were lost to fuel exhaustion after bombing their targets and the experiment was not repeated. Smaller carriers were built in large numbers to escort slow cargo convoys or supplement fast carriers. Aircraft for observation or light raids were also carried by battleships and cruisers, while blimps were used to search for attack submarines.

Experience showed that there was a need for widespread use of aircraft which could not be met quickly enough by building new fleet aircraft carriers. This was particularly true in the North Atlantic, where convoys were highly vulnerable to U-boat attack. The British authorities used unorthodox, temporary, but effective means of giving air protection such as CAM ships and merchant aircraft carriers, merchant ships modified to carry a small number of aircraft. The solution to the problem were large numbers of mass-produced merchant hulls converted into escort aircraft carriers (also known as "jeep carriers"). These basic vessels, unsuited to fleet action by their capacity, speed and vulnerability, nevertheless provided air cover where it was needed.

The Royal Navy had observed the impact of naval aviation and, obliged to prioritise their use of resources, abandoned battleships as the mainstay of the fleet. was therefore the last British battleship and her sisters were cancelled. The United States had already instigated a large construction programme (which was also cut short) but these large ships were mainly used as anti-aircraft batteries or for Naval gunfire support, shore bombardment.

Other actions involving naval aviation included:

* Battle of the Atlantic, aircraft carried by low-cost escort carriers were used for antisubmarine patrol, defense, and attack.

* At the start of the Pacific War in 1941, Japanese carrier-based aircraft sank many US warships during the attack on Pearl Harbor and land-based aircraft Sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse, sank two large British warships. Engagements between Japanese and American naval fleets were then conducted largely or entirely by aircraft - examples include the battles of Battle of the Coral Sea, Coral Sea, Midway, Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Bismarck Sea and Battle of the Philippine Sea, Philippine Sea.Boyne (2003), pp.227–8

* Battle of Leyte Gulf, with the first appearance of kamikazes, perhaps the largest naval battle in history. Japan's last carriers and pilots are deliberately sacrificed, a Japanese battleship Musashi, battleship is sunk by aircraft.

* Operation Ten-Go demonstrated U.S. air supremacy in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater, Pacific theater by this stage in the war and the vulnerability of surface ships without air cover to aerial attack.

Post-war developments

Jet aircraft were used on aircraft carriers after the War. The first jet landing on a carrier was made by Eric "Winkle" Brown, Lt Cdr Eric "Winkle" Brown who landed on in the specially modified de Havilland Vampire United Kingdom military aircraft serials, LZ551/G on 3 December 1945. Following the introduction of Flight deck#Angled flight deck, angled flight decks, jets were regularly operating from carriers by the mid-1950s.

An important development of the early 1950s was the British invention of the angled flight deck by Capt D.R.F. Campbell RN in conjunction with Lewis Boddington of the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough. The runway was canted at an angle of a few degrees from the longitudinal axis of the ship. If an aircraft missed the arrestor cables (referred to as a "bolter (aviation), bolter"), the pilot only needed to increase engine power to maximum to get airborne again, and would not hit the parked aircraft because the angled deck pointed out over the sea. The angled flight deck was first tested on , by painting angled deck markings onto the centerline flight deck for touch and go landings. The modern Aircraft catapult, steam-powered catapult, powered by steam from a ship's boilers or reactors, was invented by Commander C.C. Mitchell of the Royal Naval Reserve. It was widely adopted following trials on between 1950 and 1952 which showed it to be more powerful and reliable than the hydraulic catapults which had been introduced in the 1940s. The first Optical Landing System, the Mirror landing aid, Mirror Landing Aid was invented by Lieutenant Commander H. C. N. Goodhart RN. The first trials of a mirror landing sight were conducted on HMS ''Illustrious'' in 1952.

The US Navy built the first aircraft carrier to be powered by nuclear reactors. was powered by eight nuclear reactors and was the second surface warship (after ) to be powered in this way. The post-war years also saw the development of the helicopter, with a variety of useful roles and mission capability aboard aircraft carriers and other naval ships. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the United Kingdom and the United States converted some older carriers into Commando Carriers or Landing Platform Helicopters (LPH); seagoing helicopter airfields like . To mitigate the expensive connotations of the term "aircraft carrier", the carriers were originally designated as "through deck cruisers" and were initially to operate as helicopter-only craft escort carriers.

The arrival of the Sea Harrier VTOL/STOVL fast jet meant that the Invincible-class could carry fixed-wing aircraft, despite their short flight decks. The British also introduced the ski-jump ramp as an alternative to contemporary catapult systems. As the Royal Navy retired or sold the last of its World War II-era carriers, they were replaced with smaller ships designed to operate helicopters and the V/STOVL Sea Harrier jet. The ski-jump gave the Harriers an enhanced STOVL capability, allowing them to take off with heavier payloads.

In 2013, the US Navy completed the first successful catapult launch and arrested landing of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) aboard an aircraft carrier. After a decade of research and planning, the US Navy has been testing the integration of UAVs with carrier-based forces since 2013, using the experimental Northrop Grumman X-47B, and is working to procure a fleet of carrier-based UAVs, referred to as the Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) system.

Jet aircraft were used on aircraft carriers after the War. The first jet landing on a carrier was made by Eric "Winkle" Brown, Lt Cdr Eric "Winkle" Brown who landed on in the specially modified de Havilland Vampire United Kingdom military aircraft serials, LZ551/G on 3 December 1945. Following the introduction of Flight deck#Angled flight deck, angled flight decks, jets were regularly operating from carriers by the mid-1950s.

An important development of the early 1950s was the British invention of the angled flight deck by Capt D.R.F. Campbell RN in conjunction with Lewis Boddington of the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough. The runway was canted at an angle of a few degrees from the longitudinal axis of the ship. If an aircraft missed the arrestor cables (referred to as a "bolter (aviation), bolter"), the pilot only needed to increase engine power to maximum to get airborne again, and would not hit the parked aircraft because the angled deck pointed out over the sea. The angled flight deck was first tested on , by painting angled deck markings onto the centerline flight deck for touch and go landings. The modern Aircraft catapult, steam-powered catapult, powered by steam from a ship's boilers or reactors, was invented by Commander C.C. Mitchell of the Royal Naval Reserve. It was widely adopted following trials on between 1950 and 1952 which showed it to be more powerful and reliable than the hydraulic catapults which had been introduced in the 1940s. The first Optical Landing System, the Mirror landing aid, Mirror Landing Aid was invented by Lieutenant Commander H. C. N. Goodhart RN. The first trials of a mirror landing sight were conducted on HMS ''Illustrious'' in 1952.

The US Navy built the first aircraft carrier to be powered by nuclear reactors. was powered by eight nuclear reactors and was the second surface warship (after ) to be powered in this way. The post-war years also saw the development of the helicopter, with a variety of useful roles and mission capability aboard aircraft carriers and other naval ships. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the United Kingdom and the United States converted some older carriers into Commando Carriers or Landing Platform Helicopters (LPH); seagoing helicopter airfields like . To mitigate the expensive connotations of the term "aircraft carrier", the carriers were originally designated as "through deck cruisers" and were initially to operate as helicopter-only craft escort carriers.

The arrival of the Sea Harrier VTOL/STOVL fast jet meant that the Invincible-class could carry fixed-wing aircraft, despite their short flight decks. The British also introduced the ski-jump ramp as an alternative to contemporary catapult systems. As the Royal Navy retired or sold the last of its World War II-era carriers, they were replaced with smaller ships designed to operate helicopters and the V/STOVL Sea Harrier jet. The ski-jump gave the Harriers an enhanced STOVL capability, allowing them to take off with heavier payloads.

In 2013, the US Navy completed the first successful catapult launch and arrested landing of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) aboard an aircraft carrier. After a decade of research and planning, the US Navy has been testing the integration of UAVs with carrier-based forces since 2013, using the experimental Northrop Grumman X-47B, and is working to procure a fleet of carrier-based UAVs, referred to as the Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) system.

Roles

Naval aviation forces primarily perform naval roles at sea. However, they are also used for other tasks which vary between states. Common roles for such forces include:Fleet air defense

Carrier-based naval aviation provides a country's seagoing forces with air cover over areas that may not be reachable by land-based aircraft, giving them a considerable advantage over navies composed primarily of surface combatants.Strategic projection

Naval aviation also provides countries with the opportunity to deploy military aircraft over land and sea, without the need for air bases on land.Mine countermeasures

Aircraft may be used to conduct naval mine minesweeping, clearance, the aircraft tows a sled through the water but is itself at a significant distance from the water, hopefully putting itself out of harm's way. Aircraft include the MH-53E and AW101.Anti-surface warfare

Aircraft operated by navies are also used in the anti-surface warfare (ASUW or ASuW) role, to attack enemy ships and other, surface combatants. This is generally conducted using air-launched anti-ship missiles.Amphibious warfare

Naval aviation is also used as part of amphibious warfare. Aircraft based on naval ships provide support to marines and other forces performing amphibious landings. Ship-based aircraft may also be used to support amphibious forces as they move inland.Maritime patrol

Naval aircraft are used for various Maritime patrol aircraft, maritime patrol missions, such as reconnaissance, search and rescue, and maritime law enforcement.

Vertical replenishment

Vertical replenishment, or VERTREP is a method of supplying naval vessels at sea, by helicopter. This means moving cargo and supplies from supply ships to the flight decks of other naval vessels using naval helicopters.Anti-submarine warfare